Timpani History

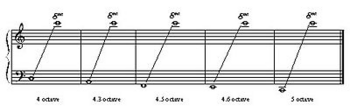

Range of Marimba | |

| |

| Yamaha 5100A | |

|---|---|

| Range of Marimba |

Introduction type here

Medieval History

Middle Eastern Origins

We first see the ancestor of the kettle drum, the naker, first emerged circa 476 A.D., during the fall of the Roman Empire, when the German barbarian Odoacer overthrew Romulus, the last of the Roman Empire Leaders. This led to the collapse of countries that relied on the Empirical system for economic purposes, as well as safety and protection. This caused a spike in poverty, and a lack of an educational system in Western Europe. However, countries in the Middle East as well as the Far East were thriving. Arabia had adopted the single-headed, closed body drum from Egypt, and adapted it to become the early naker (present in the fall of the Roman Empire), which was called the naqqāra, or nacair. A pair of nacairs would be mounted on either side of a camel, and the musician would sit and play on the camel as well. These drums measured 24 inches and 18 inches in diameter. In 622 A.D., the Middle East saw the rise of Islam, and through more unified countries, Islamic countries were able to seize Constantinople in 673 A.D., thus introducing their mounted nacair drums to Western Europe.

The Naker

The term: naker, was adopted from the Middle/Far East to the Western European countries. Due to the eastern countries quick advancements of the time, it is likely that eastern nakers were used in pairs, but there is little evidence of this technique until the drums became adopted for use in the Crusades in the 11th Century, these drums were also used in pairs in Russia and Poland. King Louis the IX (1214-1270) was one of the first of the aristocracy to use small nakers, he adopted these instruments under his rule from the 13th Century onward. Around 100 years later during the 14th Century, the nakers became the official symbol for aristocracy, they were used in musical entertainment, encouragement in the tournament, as well as being played to increase the sounds of turmoil in battle. Many artists and sculptures have depicted nakers, where they were shown suspended in the front, around the waist. Another difference from the tabor was that the naker was played with two sticks rather than one. During this time, Kettle Drums had also started to develop out of the nakers, these were essentially bowls that would be laid on the ground, where you would either sit down and play them, or bend over. It’s difficult to tell how the head on a naker or kettle drum was attached, all solutions appeared to be problematic, but were still done anyway, they would either be: nailed, rope-tied, or necklaced. Drums were made of either wood, pottery, or even copper depending on what kind of craftsmen and resources which were prominent in the area, a woodsmen, potter, or metalsmith. There was a variety of playing sticks, they would be either light, heavy, or elaborately fashioned, some however were simply crude sticks.

The Early Kettle Drum

It was during this time of the tabor and the naker that the race to who will dominate the future percussion section of the orchestra was occurring. The naker held the upper hand due to its association with the aristocracy, as well as the use of two sticks to play, when using two sticks, the embellishments could be significantly more elaborate. During the 9th Century, the Hungarians began to spread throughout the surrounding countries with their large kettle drums mounted on horses. Other countries became envious of Hungary’s drums, and began to copy them. When the King of Hungary began to travel, he would be accompanied by the largest kettle drums of the time. In the 15th Century, true kettle drums , the precursor to the orchestral timpani began to appear, and spread throughout Western Europe. When the larger kettle drums were first introduced into Germany, a priest named Virdung wrote disapprovingly of the drums. Virdung was not impressed by the boominess of the drums, or the pomp and flourishes they provided, this further pushed the church to believe percussive drums as provocations of war. However, this didn’t stop the German aristocracy from adopting the drums from Hungary. Germany later sent an embassy accompanied by their new kettle drums to France, where the French royalty was so appalled by the bombastic instruments, that they ordered the drums to be “dashed to pieces”. The kettle drums then made their way into Britain, where there is a consistently referenced record of King Henry VIII (1491-1547) specifically asking the kettle drum makers in Vienna in 1542 to create a pair of large kettle drums for him, as well as to send men that would be able to play the drums skillfully. Just as the Hungarians had carried their kettle drums on horses, the English had constructed carriages that would be attached to horses, but would allow the kettle drums to sit with a kettle drummer in the back. The drums being carried on the backs of animals were integrated at the close of the 17th Century, and were adopted by Germany as well. This tradition was likely still being carried on in the Middle/Far East Germany continued to be the best in drum manufacturing, as well as now having beat Hungary in terms of having the best kettle drummers, Germany also then created the Imperial Guilds for the kettle drums by the 17th Century. Being of Imperial title, members would hold the same ranks as military officers, and being a closed group as well this allowed the secrets of Germany’s playing technique to be passed down safely through generations. When recruiting for new guild apprentices, officers in the guild would carefully select younger people from aristocratic, respectable families. The guilds were so well enforced in Germany, that they actually had the ability to impose penalties on people who were not part of the guild if they were caught owning, or playing kettle drums. Germany is not the only place where kettle drummers of the time were persons of high ranking importance, in 1606 Portugal, there is record of a kettle drummer for the aristocracy whose title read: William Pierson, Timpanist to Prince Henry. The word timpanist had actually developed when Italy was the largest cultural center of the time, every person that had travelled to study in Italy started calling kettle drums, timpani, and it stuck until around 1600 and wasn’t widely used again until the classical era when Italian opera would call for timpani. In 1624, a kettle drummer in England held the title of: Richard Thorne, King’s Drummer. After 1661, there are various references in England referring to men as ‘His Majesty’s Kettledrummer’.

Baroque/Classical History

During the Baroque era, some composers began to write for percussion instruments in a classical manner, where the instruments were required to play notes that were written on sheet music, rather than playing in an improvisatory style. These composers included Jean-Baptiste Lully, who is famous for first writing for timpani in his opera Thésée (1675). Even earlier however, the timpani were used in Matthew Locke’s semi-opera Psyche ((1675), although this is not a very well-known piece as it was not a financial success. It was based loosely on a work of the same name that Jean-Baptiste Lully had composed in 1671. Johann Sebastian Bach was another composer who was one of the first to begin writing for timpani. His standard composition technique was to use three trumpets, with timpani, however there were some instances in Bach vast literature where the number of trumpets or the inclusion of horns changes. Some famous works of his where timpani are included are Sanctus in D Major, BWV 238 (1723), and Mass in B Minor, BWV 232 (1749). George Frederic Handel’s most famous piece, his oratorio The Messiah, HWV 56 (1741), also includes two timpani in the orchestration of two movements. The timpani would likely be played along with the trumpets, and wouldn’t necessarily have a pitch, they would serve purposes such as assisting the dynamic crescendos, and filling out the register of high’s and low’s of the trumpet sound as they transferred from tonic to dominant, which the timpani were often tuned to. The timpani during the Baroque era were generally 18 and 20 inches in diameter, and 12 inches deep. Due to the problems discussed earlier and the shallow drum, the skin used on the head, which was often calfskin, was held over the drum with less tension. This may not have produced a clear tone all the time, and in fact may have simply induced intense, non-harmonic pitches such as a high and low sound. Mallets that were used had tiny knobs at the end, which is the end you would play with, or sometimes, they would have tiny discs, these early mallets were generally made of Beech or Boxwood. For softer dynamics however, mallet heads would be covered with either chamois, or leather. Pieces that were a little more solemn, such as for a funeral may may have the mallets be covered in wool or gauze. The timpani were faced with some challenges when becoming integrated into the orchestra. Often, the timpani were the solo instrument and the composer would rely on the timpanist to realize the intent of what the composer wanted, as well as express the artistry as an individual instrument. The timpanist must also listen and find where his part fits into the orchestra, as parts that were written were often composed as though the composer had just written down what may have sounded nice and easy to play on a keyboard. One consistent technique began to happen in the orchestra however, and that is the timpani began to be placed near the brass, as the parts often lined up.

Haydn and Mozart's Timpani

During the Classical era, we begin to see the timpani dominate the percussion section. Due to the composition techniques of masterful composers, such as Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, the timpani and their players were forced to evolve. Franz Joseph Haydn in his later years began to use the timpani in expressive ways, not previously used by other composers. In 1791, in Haydn’s Surprise Symphony No. 94, he uses the timpani, employing loud notes, to reinforce the ‘surprise’ aspect of the symphony. In Haydn’s Symphony No. 103 (1795), known as the drumroll symphony (Paukenwirbel), he employs a solo timpani roll on E flat that effectively opens the piece and sets the mood. The roll is meant to sound continuous, and signified the current threat of war during the time. Later, in Haydn’s The Creation (1798), Haydn uses the timpani as a programmatic tool, using a drum roll to signify a roll of thunder. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was one of the first composers to begin using a fourth in the timpani in his compositions, rather than the started fifth. (Tonic and Dominant) He also began to use the pitches that were tuned in the higher register of the drum. It’s been speculated that the reason Mozart employed these changes was likely due to his sensitive ear. Another innovation that Mozart had added to the timpani, was for them to be performed coperti (muffled). He used this instruction in two pieces, Idomeneo (1781), and The Magic Flute (1791). In Idomeneo, there has been controversy as to whether it is the actual drum heads that should be muffled, or that the sticks should be muffled or wrapped in a soft material. Today, the performance practice is to muffle the drum heads to match the muted trumpets playing simultaneously. By the time that The Magic Flute, had premiered, the range of the timpani had increased to a ninth, a F and G. Mozart was also one of the first composers to employ four timpani, rather than two. This happened in his piece Divertimenti for Flute No.’s 5 (1783), where a key change occurs, requiring the drums that were in A and D, to change to C and G. With drums not having the ability to quickly change tuning to accommodate the key change, four drums were employed. In regards to composition, Mozart preferred the timpani roll to achieve sustain on the drums, and would often write his rolls with fortepiano attacks, as well as effectively use fortissimo, and pianissimo to set up the mood of the piece.,

Beethoven's Timpani

Beethoven would mostly use only two timpani in his writing, not because the functionality of using more was not appealing to him, but because he was able to use originality and careful composition techniques which allowed him to effectively only need two drums. Even though Beethoven would traditionally write for two drums, which were mostly tuned to the tonic and dominant in a fifth, or a perfect fourth, (Which was preferred by Mozart as well. It is speculated that these master composers used the fourth often because the closer interval helped structure the harmony more effectively than a fifth.) the timpanist performing the piece may add a third drum to accommodate either a tuning change, or match timbre between the drums. (Pitches between the drums should often be in the same register as each other, so they sound similar.) The timpani roll was often employed in the orchestra before Beethoven, for instance Mozart favored it for sustaining notes. Beethoven not only used the roll for sustaining pitches through the timpani, but he would add dynamics to it. Beethoven’s loud roll, which he introduced in Leonore No. 3 (1805), strengthened the harmonic structure of the orchestra by including the low notes of the loud timpani roll. Beethoven also employed the loud timpani roll harmonically in his Symphony No. 5 in 1808. Other pieces that Beethoven also employed the loud timpani roll harmonically in, were pieces such as Concerto for Violin (1807), and Beethoven’s Mass in C, composed in the same year. The reason Beethoven was able to accomplish the harmonies needed through the use of the timpani roll, was due to the constantly advancing mechanics of the timpani’s ability to hold a pitch. In the early 18th-Century, Handel would also use the loud timpani roll, Handel’s purpose for this technique however was for increasing the volume in tutti sections rather than harmonically like Beethoven. Now Beethoven, as opposed to other composers of the time, was constantly innovating in his timpani writing, this is especially evident with each new symphony that he writes. Similar to Handel, a common theme among Beethoven’s writing is for the timpani drums to reinforce tutti passages or to heighten the climax of a certain movement. Innovations happen as early as Beethoven’s First Symphony (1795), where he writes cross rhythms as well as dynamically extreme solo passages. In the concluding violin passage in the fourth movement: Adagio, there are 16th notes written that are played in a triple-accent feel against the timpani playing in isolated duple rhythmic passages. In the last eight measures of the movement, the timpani holds a solo accompanimental roll to the horn section as they play melodic dotted half notes. In Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony (1807), in the fourth movement: Allegro Vivace. Beethoven writes for a solo pianissimo timpani roll that alternates with the violins every two measures. The timpani would play the roll for two measures, and then the violins would play chromatic figures for two measures. The roll is used again later in the symphony as a strong musical base for increasing the structure in the harmony, as well as propelling motivic sequences. The timpani palette expands even further in Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (1808), where the drums are used as their own color in the orchestra, and due to this we begin to see the timpani slowly begin to break away from playing solely with the brass. Due to the quick speed of the tempo in some of the movements, the timpani are used as a rhythmic force, driving the music forward. Beethoven also exploits the lower register of the timpani drums to help maintain pulse, as well as provide warmth to the lower tones. It is in Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony (1808), that we begin to see programmatic materials being presented in the timpani drums. In the fourth movement: Allegro, the drums represent the roll of thunder during the ‘storm’ section of the piece. This occurs in the form of a loud roll as discussed previously. Not only effectively working programmatically, but also assisting in maintaining the harmonic structure. Also, a small surprise is written into the timpani part as well, toward the end of the fourth movement, there are four 16th notes occurring in one beat, which jettisons the orchestra into the final tutti section. The four 16th notes are meant to be forceful, loud, and unexpected, as they occur during a mezzoforte section of the music, but are marked as fortissimo. During the 18th and 17th Centuries, timpani had usually been tuned in fifths if there were two. As mentioned before, it wasn’t until Mozart and Beethoven that timpani began to be tuned to fourths, but this was about to change in Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony (1813). By this time, the timpani had grown larger in diameter and could now hold a bigger range between pitches. Beethoven utilized this, and has the two timpani tune to three different notes. F natural, D natural, and A natural, there are two innovations happening here, the first is that the timpani are tuned to their farthest interval in Beethoven’s symphonies yet, a minor sixth apart. The second, is that Beethoven uses the timpani to accommodate key change modulations during the piece, to do this, he uses the A natural as the common tone between the keys, this is one of the first times timpani had been used in this way. One of the other times being in Robert Schumann’s Concerto in A Minor (1846). Beethoven’s symphonies have broken tradition in little ways, such as having the timpani not be solely constricted to the trumpets writing all the time. However, Beethoven had been slowly breaking down this tradition, and finally in his Eighth Symphony (1814), he finally breaks the barrier completely of having the timpani being locked in with the trumpets, and instead has the drums notated as an expressive background color to the bassoons. This piece proves that the timpani can be notated as an effective bass voice to accompany not only brass instruments, but woodwind instruments as well. It is thought that by the time of the Eighth Symphony’s premiere, that the timpani drums had expanded in diameter, reaching 25, and 28 inches. Beethoven makes use of the size of these drums, by writing for the timpani to share octave F natural’s with the bassoon, as a soloistic accompaniment. Also, Beethoven once again makes use of the duple notes against triple-accent-feel composition between the violin and timpani, similar to how he wrote in his First Symphony. The culmination of Beethoven’s journey for Romantic timpani notation comes to a completion in his famous Ninth Symphony (1824). For the first time, in music that can be analyzed classically, the timpani assist in the playing of chords on the drums. With the two drums tuned to B flat, and F natural, he uses this tuning to do what he had done in symphonies previously, which was enforce the harmonic structure, but he has the timpanist play the fifth between the two drums with other instruments that would play the mediant of the B flat chord, whether D natural or D flat, regardless of the notes being played in between the B flat and F natural being provided by the timpani, Beethoven had effectively created an entire chord between the timpani and other symphony instruments. (It is important to note, that it is relatively well-known that the chief kettle drummer of King Louis the XIV court: Claude Babelon, regularly used chords on the kettle drums, but there is no surviving documentation of his compositions that can be musically analyzed.) The finale of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, the Ode to Joy is also one of two times that Beethoven has featured what, at the time, were known as the ‘turkish instruments’. In the finale, he uses crash cymbals, triangle, and bass drum. The other piece that he had written for turkish percussion was his Wellington’s Victory (1813). Beethoven makes a final great leap for timpani notation by including the drums in his introductory octave motif of the second movement, Scherzo: Molto Vivace-Presto. Not only does he use the timpani as an introductory instrument for the motif, doing this makes the timpani a strong foundation for the melodic motif, when the timpanist is able to match the volume of the other instruments involved in presenting the opening motif. Not only does he use the timpani to help introduce the motif, he repeats it multiple times in the drums during the movement to keep it fresh and consistent in the ear of the listener.